The ride from Williamsville to the Masten District in East Buffalo took about a half an hour, but it may as well have been a world away. Like much of East Buffalo, Masten was a mostly black working-class neighborhood in the inner city that was rough around the edges; though, in the early 1980s, it was not yet completely ghetto as fuck. Back then the Bethlehem Steel plant was still humming and Buffalo was the last great American steel town. Most men in the city, black and white, worked solid union jobs and earned a living wage, which meant business in Masten was good. For my dad, it always had been.

By the time he was twenty years old he owned a Coca-Cola distribution concession and four delivery routes in the Buffalo area. That’s good money for a kid, but he had bigger dreams and an eye on the future. His future had four wheels and a disco funk soundtrack. When a local bakery shut down, he leased the building and built one of Buffalo’s first roller skating rinks.

Fast-forward ten years and Skateland had been relocated to a building on Ferry Street that stretched nearly a full block in the heart of the Masten District. He opened a bar above the rink, which he named the Vermillion Room. In the 1970s, that was the place to be in East Buffalo, and it’s where he met my mother when she was just nineteen and he was thirty-six. It was her first time away from home. Jackie grew up in the Catholic Church. Trunnis was the son of a minister, and knew her language well enough to masquerade as a believer, which appealed to her. But let’s keep it real. She was just as drunk on his charm.

Trunnis Jr. was born in 1971. I was born in 1975, and by the time I was six years old, the roller disco craze was at its absolute peak. Skateland rocked every night. We’d usually get there around 5 p.m., and while my brother worked the concession stand—popping corn, grilling hot dogs, loading the cooler, and making pizzas—I organized the skates by size and style. Each afternoon, I stood on a step stool to spray my stock with aerosol deodorizer and replace the rubber stoppers. That aerosol stink would cloud all around my head and live in my nostrils. My eyes looked permanently bloodshot. It was the only thing I could smell for hours. But those were the distractions I had to ignore to stay organized and on hustle. Because my dad, who worked the DJ booth, was always watching, and if any of those skates went missing, it meant my ass. Before the doors opened I’d polish the skate rink floor with a dust mop that was twice my size.

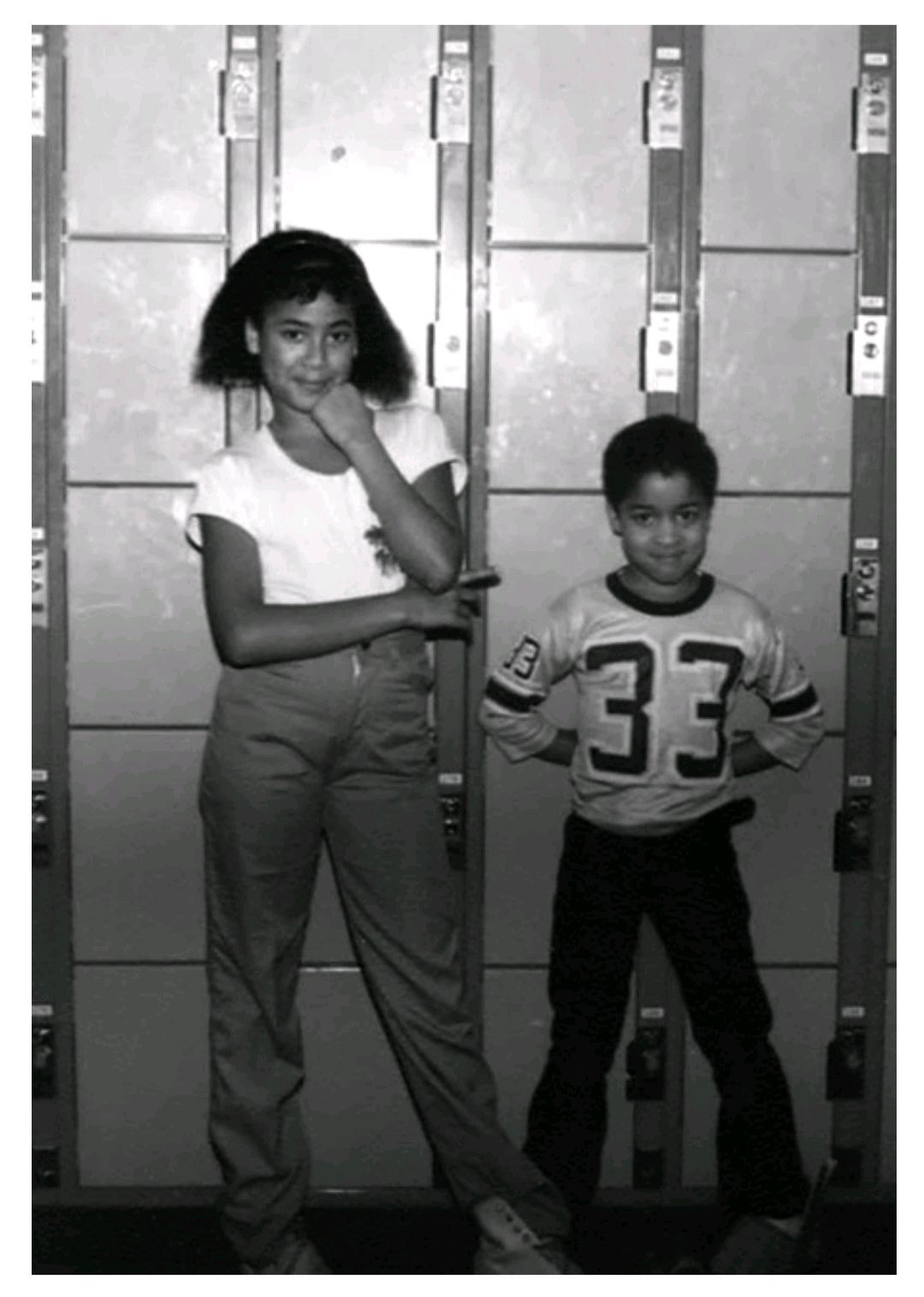

skateland, age 6

At around 6 p.m., my mother called us to dinner in the back office. That woman lived in a permanent state of denial, but her maternal instinct was real, and it made a big fucking show of itself, grasping for any shred of normalcy. Every night in that office, she’d set out two electric burners on the floor, sit with her legs curled behind her, and prepare a full dinner—roast meat, potatoes, green beans, and dinner rolls, while my dad did the books and made calls.

The food was good, but even at six and seven years old I knew our “family dinner” was a bullshit facsimile compared to what most families had. Plus, we ate fast. There was no time to enjoy it because at 7 p.m. when the doors opened, it was show time, and we all had to be in our places with our stations prepped. My dad was the sheriff, and once he stepped into the DJ booth he had us triangulated. He scanned that room like an all-seeing eye, and if you fucked up you’d hear about it. Unless you felt it first.